By Dr. Linnea Vohlberg, Institute for Mythic Cognition and Comparative Faiths

Across the vast and varied landscapes of human culture, few animals have held a position as symbolically rich and spiritually multifaceted as the cat. Revered and reviled, worshipped and whispered about, the cat has prowled the corridors of temples, stories, and psyches for millennia. Its image—aloof, graceful, nocturnal—has resonated deeply with the religious imagination of humanity, manifesting in a dizzying variety of symbolic roles and psychological projections.

To understand cats in religion is not merely to catalog artifacts or folktales. It is to enter into the psychospiritual dialogue between humans and the unknown, where the cat becomes both icon and enigma, a cipher for forces we admire, fear, and seek to domesticate within ourselves.

1. The Sacred Cat: From Egypt to Edo

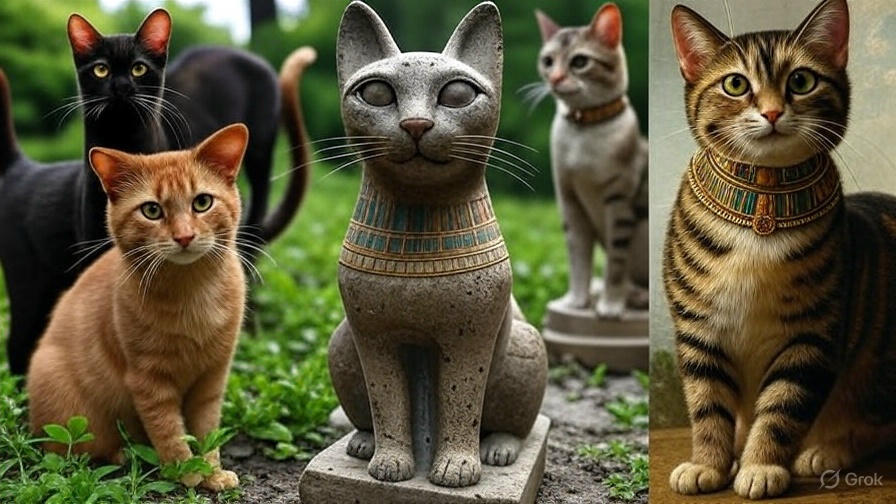

The cat’s elevation to sacred status is perhaps most famously represented in ancient Egypt, where the feline deity Bastet embodied protection, fertility, and the hearth. Cats were mummified, adorned with jewelry, and mourned with genuine grief. Killing a cat—even accidentally—was punishable by death. In Bastet, the cat represented a divine femininity: nurturing yet fierce, elegant yet capable of violence. This duality mirrored the Egyptian theological tendency to deify balance—chaos and order, life and death—within a single form.

In medieval Japan, cats took on an almost guardian-like role in folklore and religious life. The maneki-neko, or “beckoning cat,” emerged not just as a good-luck charm but as a figure woven into Buddhist narratives. Cats were believed to protect sacred texts from rodents and evil spirits, and in some Zen traditions, their silent presence became metaphors for stillness and self-contained enlightenment.

The cultural context here is key: in societies where silence, interiority, and balance were valued, the cat’s seeming detachment became spiritual shorthand. The feline became a symbol of inner poise and the unknowable soul—a “living koan” that resisted human interpretation and, therefore, invited contemplation.

2. The Demonization of the Cat: Fear, Femininity, and the Shadow

But not all cat imagery is beatific. In medieval Christian Europe, cats—particularly black ones—were entangled in the imagery of witchcraft, heresy, and the devil. Their nocturnal habits, glowing eyes, and perceived unpredictability aligned them with the religiously coded “Other”: women, pagans, heretics, and Jews were all, at times, accused of “consorting with cats.”

The psychological underpinning here is striking. Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow archetype—the repressed parts of the self—offers one lens. The cat, autonomous and defiant of control, symbolized what structured, patriarchal societies could not tolerate: the wild feminine, the creature that chose affection but never obeyed. In burning cats alongside witches, society attempted to purge itself of this shadow—but, of course, repression only deepened the cat’s mythic power.

3. Modern Mysticism: Cats in Contemporary Spirituality

In the 20th and 21st centuries, cats have reemerged in a more benign spiritual light—particularly within New Age and internet-era mythologies. The proliferation of cats in memes, gifs, and social media may appear trivial, but many cultural theorists now argue that this represents a form of digital totemism. We watch cats, follow them, even confess to them. They are our shamans of soft chaos in a pixelated world.

In spiritual subcultures, cats are regularly cited as energy-sensitive beings, capable of detecting auras, calming anxiety, and serving as emotional familiars. Pagan and Wiccan communities often reclaim the cat as a companion in magical work—not a servant, but a partner. The emphasis is on relational autonomy: the cat does not obey commands but enters into symbolic cooperation.

Theologically, this points to a post-hierarchical spirituality, one that values presence over power, intuition over dogma. The cat becomes a spiritual co-presence—not a messenger of gods, but a godlet in her own right. In contemporary rituals, the cat is not sacrificed, controlled, or moralized. She is watched.

4. Conclusion: The Cat as Mirror of Human Longing

The spiritual life of the cat is ultimately a reflection of human desire—for mystery, for companionship that does not require possession, for the comfort of silence, for the presence of the divine in the mundane. Across cultures and centuries, cats have embodied paradox: sacred yet irreverent, sensual yet reserved, domestic yet ungovernable.

In studying how we have imagined cats, we learn how we have imagined ourselves—and the gods we long for: not omnipotent rulers, but quiet, watchful beings who sit just at the edge of the firelight, blinking slowly, asking nothing, offering everything.

Dr. Linnea Vohlberg is a cultural historian and psychologist specializing in animal symbolism and contemporary ritual practice. She is the author of “Paws of the Infinite: Animals in the Post-Secular Imagination.”

Leave a comment