By Dr. P. Linquistica Merengue

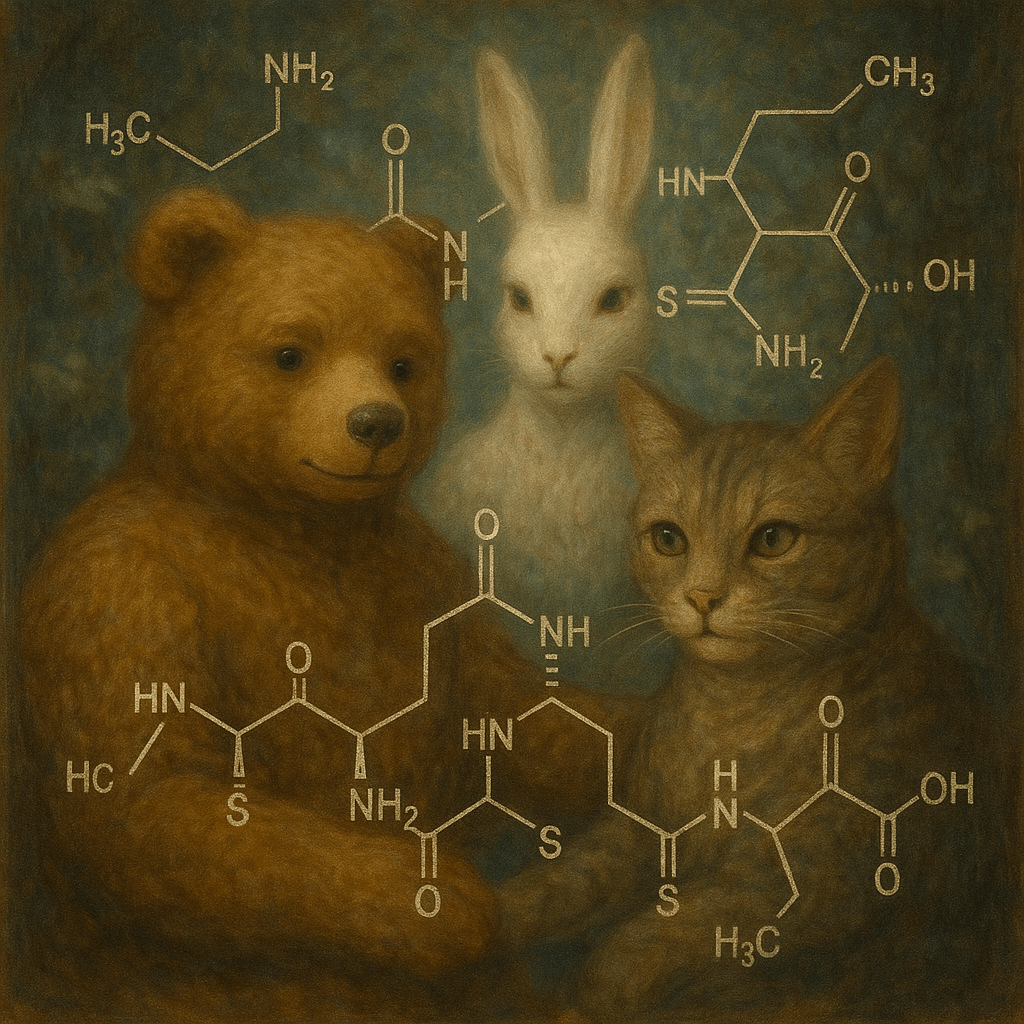

The anatomical and cognitive divergences between the brains of Ursus Plushii (commonly referred to as teddy bears) and Felis Anthropomorphica (the socialized domestic cat) have been a point of considerable speculation in the field of semiotic zoology. While neither organism possesses a traditional biological brain in the neurophysiological sense, their metaphoric and symbolic cranial structures have been mapped extensively in the disciplines of affective computation and plush neuroscience.

I. Structural Mythoneurology

Teddy bears, constructed primarily of hypoallergenic polyester stuffing and emotional resonance, exhibit what scientists refer to as a “Limbic Loop of Comfort.” This cognitive zone, non-locatable on standard imaging, is activated by cuddles, bedtime stories, and the whispered fears of children. MRI analogues reveal a spiraling, non-Euclidean topology that supports a near-infinite capacity for silent listening.

Cats, on the other paw, possess a “Neuro-Mystic Cortex,” often referred to as the Zone of Calculated Disdain (ZCD). This area appears to self-replicate when confronted with tasks, commands, or human expectations. It is structurally fuzzy, yet tactically precise. Synaptic firings often resemble jazz rhythms: unpredictable, smooth, and with a touch of menace. The feline brain has a notable Sulcus of Superior Superiority, present from birth and resistant to external stimuli.

II. Thought Velocity and Emotional Processing

Teddy cognition moves in slow, deliberate loops—similar to Gregorian chants or honey dripping through wool. Thoughts are diffuse, emotionally saturated, and scented faintly of nostalgia. These beings operate via a high-latency, low-reactivity empathy matrix. Every external input is filtered through a fabric-based Sentiment Amplification Chamber.

Cats, however, exhibit quantum-thought twitching. Ideas flicker in and out of focus, existing simultaneously as laziness and tactical readiness. Emotional responses are not stored but launched, sometimes with claws. The cat’s brain includes a subcortical region termed the Ego Kernel, which is laminated in smugness and occasionally resonates in the presence of open laptops or freshly folded laundry.

III. Memory and Dream Functions

Teddy bears do not dream; they absorb dreams. The Dream Sponge Theory (DST), first proposed in 1973 by imaginary neurologist Babette Snaarl, posits that teddies act as passive collectors of human subconscious projections. Their memory architecture is fuzzy, sticky, and unable to forget. This makes them the most reliable mnemonic companions of childhood trauma and joy alike.

Conversely, cats have vivid REM-phase experiences, often involving the conquest of galaxies made of string, confrontations with other cats that once walked on their street, or morphing into smoke to evade philosophical inquiry. Their hippocampus is looped through the aesthetic center, leading to memory storage based on dramatic potential rather than factual integrity.

IV. Social Synaptic Behavior

Teddy brains are wired for universal co-regulation. The cortex glows slightly in the presence of human loneliness. Teddies do not require conversation; their communication is auratic, taking place in an ambient language of presence.

Cats, meanwhile, are transactional in their social neural activity. Synaptic bridges light up only in conditions that favor their self-interest. However, evidence suggests a complex and highly encrypted empathy dialect—observable only when their human is ill, sad, or pouring cereal.

Conclusion: Dualities of Symbolic Sentience

While both teddy bears and anthropomorphic cats occupy highly stylized roles within the semiotic unconscious of postmodern humans, their cerebral mythologies could not be more different. Teddy bears anchor, absorb, and pacify. Cats provoke, prance, and pounce.

The teddy mind floats on a soft sea of dream, while the cat mind darts through the constellations of instinctual mischief and surreal elegance.

Further research (funded by plush grants and feline crypto assets) is required to fully model these entities in augmented-reality simulations of psychological ecosystems. Until then, their differences will remain felt but not fully known—like the warmth of a paw, or the wisdom of a stuffed silence.

Leave a comment